In nature, honey bees overwinter in hollow tree cavities, typically with a small entrance and a generous amount of insulating material above, below and around them. This creates an environment that retains heat and protects the wintering cluster from the elements, while also allowing the bees to control ventilation within the hive.

In the less natural surroundings of a beehive, the entrance and size of the hive is dictated by the choices made by the beekeeper. Bees are placed in structured, wooden hives with walls typically less than an inch thick, without the same levels of insulation bees would seek in nature.

Despite these differences, bees both in the wild and in beehives can and often do survive the cold months. But, as with all things beekeeping, getting your bees through the winter comes down to an evaluation of pros and cons, finding the right balance for your bees in your locality. What exactly is the “right” type and level of insulation necessary?

Let’s take a look at beehive insulation for the winter.

Bees and Temperature

How the Cluster Changes with Temperature

Once temperatures drop into the 50s (Fahrenheit), a honey bee colony will start to cluster, to conserve heat and to protect the queen. This survival mechanism reduces the surface area of the colony and thus it’s external exposure to cold air. Around 40 degrees, the colony experiences a very low metabolic rate. Because of this they will consume the least amount of stores, compared to what we see at other temperatures. In fact, beekeepers who overwinter indoors in a temperature-controlled environment seek to maintain a temperature of around 40 degrees, for just this reason.

Once temperatures fall below 40 degrees, however, bees deploy another tactic. Bees inside the cluster start to vibrate their wing muscles, in an attempt to generate heat and keep the interior of the cluster warm. Bees on the outside, exposed edge of the cluster will be largely still, acting collectively as an insulation layer. No direct attempt is made by the cluster to raise ambient temperature within the hive. Their actions are all about maintaining a survivable temperature within the cluster, with the primary focus on protecting the queen. The colder it gets, the greater the requirement to consume stores, with energy needs increasing as bees attempt to keep the cluster at an acceptable inner temperature.

The Path of the Cluster

In terms of the position within the hive, the cluster will normally move upwards in the hive over the course of the winter, They will consume resources from the store as they do so. The goal here is to make sure they don’t run out of stores as they do so.

By the way, it is not uncommon for a colony to starve even with abundant resources in the hive. The cluster needs to be able to get to those resources and if there is a broken path of viable resources while temperatures remain low, the cluster may not be able to cross that gap. This is why many beekeepers rearrange frames with honey stores in the fall, to help the cluster find that continued path.

Some beekeepers place a sugar fondant or even dry granulated sugar in feeders on top of their overwintering boxes, just in case. The opposite is true as well. The warmer it gets from the 40s the more energy the bees require. Typically however, this fortunately coincides with spring and summer weather where bees can fly and go get those additional needed resources. In cold temperatures, insulation will assist the bees when it comes to maintaining the temperature of the cluster.

Condensation: Good and Bad

Once you’ve insulated a hive the environment becomes much more controlled. Condensation will be more likely to occur in non-insulated areas of a hive. Many beekeepers subsequently ventilate well-insulated hives less in winter, as condensation has been managed. That said, while managing condensation is one thing, you don’t need to go overboard and attempt to eliminate it.

Cold air can’t hold much moisture. Therefore when the heat from the cluster interacts with cold air within the hive condensation can form. This condensation can even turn into accumulated ice in the hive in very cold environments, and in some circumstances can drip down on top of the cluster. Either case is to be avoided.

Bees still need water in the winter and condensation may be how they get it when they cannot fly. This water can be used to rehydrate honey crystalized in combs, helping to sustain a winter colony. What is to be avoided at all costs in condensation forming above the cluster, subsequently dripping back down on the bees. Some ventilation will be required no matter how insulated your hives are. Make sure your bottom entrances don’t become blocked by snow, one more benefit of using a hive stand.

Space Management

No matter if you choose to go with insulation or not and no matter your type of hive, going into the winter with the right configuration of hive is also important. Just like a large house for a large family, more boxes are needed for larger hives and fewer for smaller hives. However, it takes more energy to heat that large house in the winter no matter how well it’s constructed or insulated.

Bee hives are no different. Putting five frames of bees into triple deeps, as one extreme, would be so much space, that even in a well-insulated hive, the cluster would have to work harder to stay warm. On the other hand, putting a large hive into a single deep could leave them without enough resources to make it through the winter in colder climates.

It’s all about finding the right balance for your climate and your bees. While bees are not seeking to heat the internal space of the hive (only the cluster), any heat retained within the hive will mean the bees will not have to work as hard to keep the cluster warm.

A Traditional Setup

Traditional methods of overwintering your hives often involve setting up hives with maximum stores and maximum ventilation. To combat this many beekeepers utilize both bottom and upper ventilation throughout the winter in an effort to increase airflow in the hive to evacuate this humid air. To increase ventilation even more, some beekeepers will go one step further and utilize a fully screened bottom board all winter long.

The “chimney effect” setup is proven to work and results in a good exchange of air. However, as the bees have to work harder to maintain the temperature of the cluster they will consume more stores. More honey will need to be left on the hive in the fall. You may also need feed in the fall and again in the spring.

Insulating Hives & Insulated Beehives

Is there a better way? How can we, as beekeepers, help? Just like your house is insulated and (hopefully) is not raining down with condensation during the winter months, insulation can be used strategically to retain heat in a beehive without increasing condensation (when combined with appropriate ventilation).

Quilt Boxes

One way to add insulation to the top of a hive is by using a quilt box. Typically this is another box placed on top of your brood boxes for winter that beekeepers usually fill with wood shavings or sawdust. Heat rises from the cluster, and the condensation point should now occur either within the layer of shavings or above the shavings on the inner cover. Either way, the wood shavings or sawdust will in turn absorb this moisture.

Quilt boxes are usually vented so that on nice days, this moisture can then evaporate. To a lesser extent, insulated outer covers and / or insulated inner covers can offer some of the same insulation, but without the moisture-absorbing ability of a quilt box.

Hive Wraps

Another option for winter hive care and specifically to insulate your hives, is by using a hive wrap. These are insulated wraps that wrap around your entire hive to help insulate the sides. The more insulation, the less the bees have to work to maintain the temperature of the cluster, and less work means less stores consumed.

Traditionally, beekeepers have used everything from roofing tar paper to hay – or even snow in particularly frigid areas to achieve the same effect. Today, the beekeeper that is looking to insulate a standard wooden hive is more likely to use an off-the-shelf hive wrap or make their own out of foam board insulation from the hardware store.

Hives that are already insulated are another option. In fact, some of Langstroth’s original hive designs were double-walled hives, and beekeepers have been experimenting with insulated hives for a very long time. In Langstroth’s 1852 patent for example, it was suggested to insulate areas of the hive in winter “with sawdust, or some other good non-conductor of heat” so that “greater protection may be given”.

Insulated Inner Covers

Another increasingly popular option is the use of insulated hives components, such as the Insulation Top Cover, the BeeMax Top Cover and the BeeSmart Insulated Cover.

Slatted Racks

A hive accessory that is not commonly used, but can be useful for both space and temperature management is a slatted rack. This is essentially a very shallow box, a couple of inches in height, that you place underneath your lowest brood box and above the hive entrance.

The slatted rack creates a static air space between the entrance and the outside of the hive, and the lowest part of the brood nest and bottom of the frames. By doing so you create more space for cold air to sink and provide further protection from direct drafts.

Some say this also helps throughout the year – by allowing a space inside the hive for bees to occupy in hot weather, and it is also said that with the bottoms of the combs now more protected, a queen will utilize more of the lower parts of the frames to lay.

Please see “A Guide to Slatted Racks” for more details.

R-Values

Today, most insulated hives will use some type of synthetic insulation in their construction to achieve a higher level of insulation than that of standard wooden hives. It all comes down to the r-value – a measure of a material’s resistance to heat transfer. The thin walls of standard hives, made from boards less than an inch thick, have an r-value of less than 1. Most insulated hives will have an r-value of 5 or higher already integrated into the hive, a closer value to an actual tree cavity that would be utilized by wild bees.

Hive Location

Regardless of whether you choose to insulate your hives or not, your apiary location is another factor that should be considered. A southern exposure will allow for more solar heating during the day, and you’ll also want to avoid placing your hives in low spots where the coldest of the cold air tends to settle at night.

Wind breaks, natural or man-made will be helpful as well, as wind steals heat. Some beekeepers that have multiple hives will push their hives all together for winter in a line or cluster, to help with wind and heat loss.

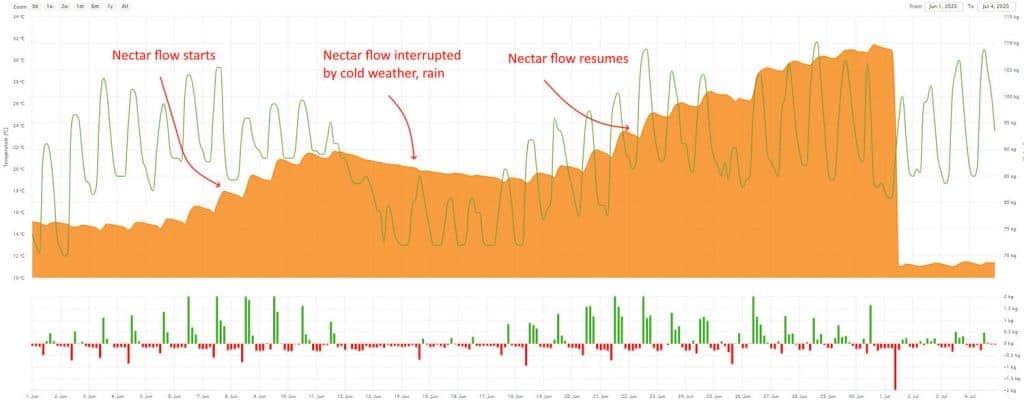

Monitoring Success

While a colony that successfully makes it through the winter is the only sure way to know how your winter hive setup really worked out, studious beekeepers can also monitor their hives throughout the winter. Electronic sensors can be used to monitor everything from weight to temperature to humidity, even going so far as sending this data right to your smartphone.

For a more old-fashioned method, a stethoscope can be used to determine the cluster’s location in a hive. Another option is to use a FLIR thermal imaging camera, that will show the temperature of the hive, the location of the cluster, and will help you identify areas of the hive that are losing the most heat.

Whatever you do, do not open the hive in cold weather, to avoid disturbing your clustering bees as much as possible.

In Short

So what are the key points to consider when considering insulation of your beehives?

- When temperatures drop into the 50s and below, the colony will cluster. Bees do not attempt to heat the hive, only the cluster. However, insulated hives will reduce the effort required of the colony and result in fewer stores consumed over winter.

- Insulation can be achieved by using insulated hives, hive wraps, or homemade solutions.

- Condensation can be managed through either more ventilation or more insulation.

- As is true during all times of the year, hive space should be a good match for the size of the colony.

- Other factors should be considered, from apiary location to optional equipment such as slatted racks.

- Monitor success with various high tech and low tech tools.

There is no definitive best way to set your hives up for winter and it’s a topic that cannot be painted with a broad brush. A beekeeper in Texas will face a very different set of challenges than a beekeeper in Maine. However, through research and discussion with local beekeepers or other beekeepers who reside in a similar climate, a beekeeper can identify the challenges a hive will face during the winter and come up with a game plan to address those challenges.

Over time, that game plan can be refined each season. There are no sure bets in beekeeping. However, once you’ve determined and perfected your system a beekeeper can take solace knowing that they’ve done the best they can do to get their hives through the winter season ahead.